A “survival of the fittest” mindset will lead us to our extinction

Survival of the fittest often leads to extinction, even for those at the top – in biology or otherwise

Survival of the fittest often leads to extinction.

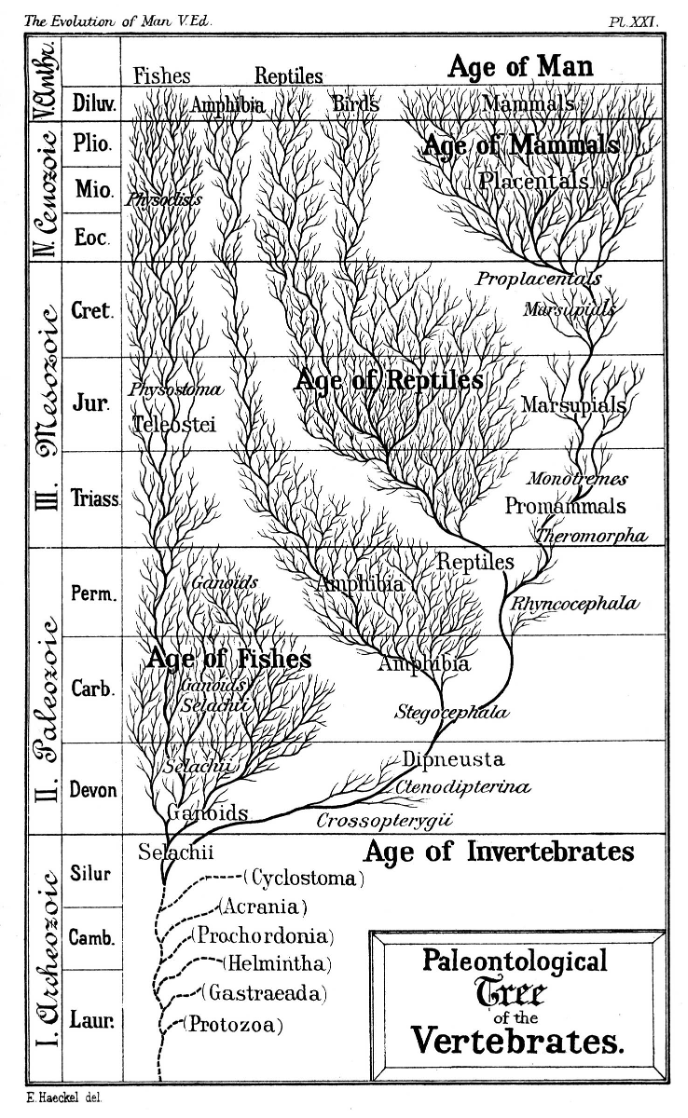

This isn’t controversial. In fact, it’s half the point of natural selection: in nature, individuals and even entire species compete against each other for access to resources, with those which are adept at surviving and reproducing successfully passing their genes to the next generation. The other side of this coin, necessarily, is that those which are less well adapted are eliminated from the gene pool and become extinct.

This is just as true for competing species in biology as it is for competing businesses in an economy. Competing for a different set of resources, true, but the same forces can be seen at work: survival, propagation, reproduction, evolution and extinction.

In both cases, the environment is constantly changing – as a result of increased competition for resources, changing dynamics between competing entities, or even from natural catastrophes. It might seem counterintuitive, but, as a result, evolution can often push otherwise successful species towards their own extinction by driving them into evolutionary dead ends – and we humans are not exempt.

Evolutionary dead ends

By evolutionary dead ends I’m referring to adaptations that are selectively advantageous in the short term but ultimately result in overspecialisation, lowered diversity, and ultimate extinction.1

Put another way, prioritising short-term gains over long-term success can often lead you down a dead end – with no way out. And since time only marches in the forward direction, there’s no turning back to find a different route.

Evolution is blind – it cannot see the future. It can only operate in the present (which is built upon what has happened in the past). And sometimes the adaptations which are beneficial and a cause for success in the short-term in the immediate environment can lead to extinction when that environment changes.

On a micro level, it is usually misadaptation that causes the extinction of individual gene lines within a species – for example, a deer whose genes have failed to equip it with the ability to properly process food will quickly starve to death before it is able to pass those genes to any offspring.

This is what people most often imagine when considering “survival of the fittest” – there is clearly a benefit to the wider population of the species when harmful genes are eliminated from the gene pool. I certainly wouldn’t want to inherit an inability to digest food from my parents.

But that’s the individual level – what about the population level? More than 99.9% of all species that have ever lived have gone extinct. How does an entire population that was once well-adapted to its environment go extinct? The chance of an entire species giving its offspring a fatal gene within a single generation is astronomically unlikely under normal circumstances. However, any species that cannot adapt to survive and reproduce in its current environment, and lacks the ability to find a new, better suited environment, will go the way of the diplodocus and the dodo. And we can learn a lot from those that didn’t make it.

Competition and Predation

The most obvious ways that entities like species or organisations go extinct – the ones which are most common in the cutthroat world of modern business – are through competition and predation. We’re all familiar with how Walmart and other large supermarkets squeeze out smaller rivals by using economies of scale and market dominance to undercut prices, or how Facebook predated upon its rivals Instagram and WhatsApp to prevent competition, or how Netflix used a new business model to outcompete Blockbuster into extinction. The same dynamics are present in nature.

Just as with Netflix and Blockbuster, when a challenger species moves into the same niche as an existing species, then the species which is better at acquiring and maintaining access to resources is the one which survives. The winner keeps its place in the niche, and the loser finds a new niche – or dies out.

The best examples of this can be found in the litany of extinct large predators our human ancestors left in their wake as they migrated across the surface of the Earth on the great diaspora out of Africa. Smilodon, the North American sabre-toothed tiger2 was one such casualty.

The sabre-toothed tiger, let us not forget, had evolved to be the most terrifyingly efficient predator on the planet, investing resources into killing its prey as quickly as possible, both through its physical attributes (its terrifying giant teeth, its large size) and its hunting behaviour (assumed to be a fatal stabbing bite to the throat). This is thought to be due to the evolutionary pressure of competition over the carcass from other large predators (including mountain lions, dire wolves, and other sabre-toothed tigers) – if you kill your prey quickly, you have more chance to recover the calories you spent killing it before other predators move in to challenge you for the meat.

But none of that mattered when the humans arrived.

Smilodon’s favoured prey animals were things like ground sloths, horses, mammoths, and bison. When homo sapiens migrated into the Americas around 12,000 years ago, an apex predator which had developed advanced collaborative hunting strategies with projectile weapons, all of these prey species – save the bison – mysteriously disappeared. It doesn’t take a detective to work that one out.3

For the prey species, predation from a supremely effective new predator wiped them out. While humans may not have hunted every last giant sloth, our impact was enough to create genetic bottlenecks, reduced mating opportunities, and other ecological shifts that directly contributed to the eventual extinction of the American megafauna.

But for Smilodon, it was competition that led to its demise. Before this, the sabre-toothed tiger was perfectly adapted to its protein-rich environment, filled with giant prey animals. But when competition from humans arrived – much more effective at hunting its food sources – the whole species Smilodon starved to death, one individual at a time.

In the world of business, this type of competition is often seen as a good thing – removing obsolete industries allows the evolution of the social and economic landscape, with more efficient and valuable organisations emerging as the victor. But the danger occurs when we ignore the wider social context in which business takes place.

Obsolete industries often find ways of hanging on, fighting back on terms outside the strict limits of the free market. Unlike Smilodon, businesses under threat of extinction can fight back by, for example, buying politicians, or publishing misleading propaganda, or bypassing regulations to gain unfair advantages. The tobacco industry fought for decades to suppress scientific evidence linking smoking to cancer and lobbied extensively to delay regulations – a strategy then copied by the fossil fuel industry to obscure the link between atmospheric warming and fossil fuel emissions. And when Uber began to disrupt the traditional taxi industry, taxi companies fought back – not by improving their services or lowering their prices, but by lobbying for stricter regulations on ride-sharing services to preserve market dominance in spite of the shift in consumer preference.

History – and even the present moment – is littered with examples like this. Perhaps that reinforces the point. Businesses and organisations are able to adapt in their own short-term self-interest (whether or not that helps or harms everyone else), whereas Smilodon was too specialised in its niche – hunting large, high protein prey animals – and once that niche was gone, thanks to competition from humans, the calorie-intensive adaptations which had made it previously so successful were what led to its extinction. Overspecialisation is a great way of getting stuck in a dead-end. Just ask Blockbuster. But it’s not always competition from other species that cuts off the path ahead – sometimes, the environment changes too quickly for a species to keep up.

Overspecialisation in a changing environment

Overspecialisation in a changing environment is the most obvious way of going extinct, and it’s most obvious because humans have been the cause of that changing environment for most other species on Earth over the last 12,000 years (since the approximate advent of agriculture).

The panda is the perfect illustration – it’s become so exclusively dependent on bamboo (which makes up 99% of its diet) that its survival as a species depends on the rapidly diminishing availability of bamboo forests (due to widespread human-led deforestation). But, at the time, when panda ancestors first started eating bamboo, they probably thought they were onto a winner – hardly any other species eats bamboo (because it’s hard to digest, contains cyanide, and has low nutritional value), so when the first proto-pandas found they could eat bamboo without getting sick, they had an entire ecological niche essentially to themselves.

By entering a niche which gave it an advantage in the short-term, and then overspecialising into that niche, the panda is now on the road to extinction. Only human largesse keeps it alive – they’re lucky they’re cute.

Humans haven’t been responsible for every instance of the environment changing though. Take trilobites – marine arthropods (cousins of modern crabs) that were adapted to live in shallow sea shelves. These creatures thrived in shallow coastal waters for over 250 million years, but when sea levels dropped during the Permian mass extinction 252 million years ago, their habitat disappeared, and they were left without an ecological niche – which is fairly terminal.

Even the most legendary shark that ever lived – Megalodon – is thought to have gone extinct thanks to overspecialisation. Apex predators are particularly vulnerable to environmental changes (climate shifts, habitat loss, changes in prey populations) because they require large territories with a stable food supply and have low reproductive rates (bigger animals take longer to grow). Their evolutionary strategies work well in stable conditions but are extremely vulnerable when those conditions change.

Just as these species blindly followed the easiest path ahead of them, and it led them to overspecialisation and possible extinction, the same is true for human societies and economies. Just take a look at some examples from our history.

Economic overspecialisation

Let’s start with the most fundamental aspect of human civilisation – agriculture. With no agriculture, there is no way to support specialisation of roles, and we all have to take up hunting or gathering as our primary profession – or find somewhere else to live. In essence, civilisation collapses.

The Mayan civilisation built extensive urban centres dependent on drought-vulnerable maize, which is thought to have contributed to societal collapse around 900 CE when climatic conditions changed.

The Irish Potato Famine, which decimated the population of Ireland from 1845 to 1855, was driven largely by an over-reliance on a single species of potato (the Irish Lumper), leading to drastically increased vulnerability to the potato blight which wiped it out.

And in the Great Plains of the 1930s US, conversion of grazeable grasslands to exclusively crop-based agriculture (combined with mechanised farm equipment to destroy the topsoil) created the Dust Bowl, which devastated the region and led to the displacement of around 3.5 million people.

The most efficient process for creating food in the short-term – the one you would expect to settle on by following a short-term, survival of the fittest mindset – ended up creating a single point of failure in the economy which led to societal collapse.

This principle does not just apply to agriculture. Take the Kingdom of Dahomey — during the 17th and 18th centuries, Dahomey became heavily involved in the transatlantic slave trade with European powers, particularly Portugal and Britain. This activity was so profitable that the economy of Dahomey became increasingly dependent on capturing and selling slaves from neighbouring territories. As the demand for slaves increased, the kingdom experienced political instability, as local leaders turned against each other to supply slaves to European traders; the primary driver of the kingdom’s economic activity was linked to the capture, sale, and export of slaves. This meant that when Britain outlawed the slave trade in the early 19th century and began enforcing this ban, Dahomey instead transitioned to a less lucrative plantation-based economy, using their slaves to harvest palm oil. This led to economic decline and the weakening of Dahomey’s political structure. It was over-reliant on a single source of wealth – one which, to add to the mix, required the continuation of violence and subjugation in order to extract value – and this led to the state’s eventual collapse.

This is comparable with the economy of the Soviet Union – in the 1980s, approximately 20-30% of the Soviet Union’s GDP and around 50% of its foreign exchange earnings were linked to the production of its energy sector, based on its large reserves of oil and natural gas. This heavy reliance on fossil fuels made its economy highly susceptible to global oil price changes, and when the oil price collapse happened in the late ‘80s, this dealt one of a series of fatal economic blows which contributed to the Soviet Union’s demise.

All of these examples illustrate an important point — reduced diversity is just as fatal to long-term success for a system (like agriculture or an entire economy) as overspecialisation. And nowhere is that more apparent than with genetic bottlenecks.

Genetic bottlenecks

Genetic bottlenecks occur when the genetic diversity of a population shrinks so much that it is incapable of adapting quickly enough to a changing environment, usually due to a sharp reduction in the size of a population. As an example, the American bison – one of the only prey animals from Smilodon’s era that survived to the present – was famously reduced to mere hundreds of individuals in the late 1800s, once human hunting techniques had moved from sharp pointy sticks to horseriding and guns.

A narrow gene pool is a bad thing – just ask the Habsburgs. A wide gene pool means a greater variety of genetic traits in a population, meaning that a species is better able to adapt to a changing environment and resist disease, and is less susceptible to the buildup of harmful mutations and even extinction events. The inverse is true – lack of diversity creates a fragile system which is less able to bounce back and survive into the future. This is true of all complex systems – ecologies, economies, neural nets. In such systems, uniformity is fragility as narrower strategies are more vulnerable to disruptions or changes in the environment. In contrast, diversity is resilience because there is no single point of failure. It’s the same reason sensible investors diversify their portfolios rather than putting all their eggs in one basket.

The best example of this in the modern economy is the over-reliance on a small handful of large companies to service the digital infrastructure of our modern world – insurers estimate that the relatively minor CrowdStrike global technology outage will have cost US Fortune 500 companies $5.4 billion.

But it’s deeper than that. Forget CrowdStrike – what about SunStrike? What will happen when the next Carrington Event-level solar flare creates a geomagnetic storm that fries our electrical grid? Our satellite systems, our communications infrastructure, our healthcare systems, our financial system, our agricultural systems, our transport and logistics… everything in our modern economy relies on a functional electric grid and the connecting power of the internet. It’s expensive to protect our infrastructure against an event which only happens once every 200 years or so, but by prioritising short-term gains, we leave ourselves vulnerable to catastrophe.

But there are much bigger catastrophes than that.

Mass extinctions

The non-avian dinosaurs dominated the Earth for hundreds of millions of years. They existed in diverse forms, from tiny, agile Compsognathus to enormous sauropods like Argentinosaurus, specialising into a wide variety of ecological niches and adapting through multiple changes in climate and environment through the Triassic, Jurassic, and Cretaceous eras. Their diversity of forms contributed to their long-term success, yet each individual species was specialised into its own particular niche. Certain species were so perfectly adapted to their environments – and their environments were so stable – that their forms barely changed for millions of years.

Take the sauropods – grazing in clearings, away from the protection of a trees with plenty of places to hide – is a risky move, as makes you much more visible to predators. Only large animals could get away with this – if you’re big enough to cause fatal damage to any predator that tries to attack you, you can graze uninterrupted in ecological niches that smaller herbivores cannot access. Once fully grown, this strategy works incredibly well against every predator which relies on close quarters attacks, which is basically everything except humans. It goes to show how being successful is dependent on the other species in your environment; if sauropods had survived to the present, they would have probably gone the same way as the mammoths and ground sloths. Fitness is entirely context-dependent.

But they didn’t get the opportunity to last that long. An act of pure destruction lobbed at them from space transformed their environment so dramatically and suddenly, each individual species was no longer the best suited to survive. In the super nuclear winters that followed the cataclysmic meteorite impact and subsequent volcanic eruptions, with limited sunlight and bitter cold, the plants they depended on for food withered and died.

Once the primary food source had gone, the herbivores died soon after – especially those with large calorie requirements (a human needs around 2,000 calories per day, a horse needs at least 20,000; large sauropods may have needed up to 200,000). And when the herbivores had all starved to death, the carnivores weren’t far behind. It’s hard to imagine a T-Rex burrowing underground to survive on insects.

Within the space of years, entire ecosystems had been wiped out before the impact winter eventually subsided. And that’s the point – mass extinctions dramatically reduce diversity in a catastrophic irreversible simultaneous systems collapse. Once the last breeding pair of a species is gone, there is no way back.

The dinosaurs went extinct, essentially, because they could not see the future.

And that’s where we are today. In the Anthropocene extinction, extinction of species is occurring at up to 1,000 times the background rate. This mass extinction is happening because of the rapid global environmental change that we are collectively causing – many species just can’t keep up. Unlike the dinosaurs, we have the ability to see the future, but our political and economic frameworks and institutions lack the adaptability to be able to course-correct quickly enough. We are causing irreversible systems collapse in multiple spheres long before we have the technology to reverse the damage – you only need look at the woeful progress the oil & gas industry has made in direct air carbon capture, which is currently more of an exercise in greenwashing than a serious attempt to decarbonise fossil fuel-derived energy production.

I just hope we don’t add our own species to the list that doesn’t make it through the Anthropocene extinction. So, what can we do to avoid that?

Can we avoid our own extinction?

The way to avoid extinction is by avoiding the pitfalls that lead into dead-ends – planning for long-term success rather than merely pursuing short-term advantages, and prioritising diversification instead of overspecialisation. And yet, our economic model and the political systems which support it are all focused on short-term gains over long-term success, driven in large part by a survival of the fittest, winner-takes all mindset. This leaves to precisely the outcomes we should be seeking to avoid:

By overspecialising our economy, especially on fossil fuel-based energy generation and financialisaton, we leave ourselves vulnerable to a full systems collapse, like those experienced by Dahomey or the Soviet Union, if (or rather when) these industries fail. The fossil fuels will dry up, and we’ve seen enough financial crises within our lifetimes to expect more.

The most powerful corporations and individuals grow their wealth due to economies of scale and warp governing systems to create and reinforce monopolies and oligarchies, suffocating competition, reducing the diversity and adaptability of the economy and increasing its fragility.

By focusing on short-term gains instead of long-term thinking, our economic model leaves us unable to plan strategically ahead and leaves us at the mercy of a changing environment. All tactics, no overarching strategy. And this is especially critical when the environment is changing so quickly.

The role of government should be to create the guardrails in which the free market can flourish, preventing monopoly and ensuring that new entrepreneurs and challenger businesses have the chance to enter the market and force the existing large businesses to adapt and compete. Instead, those large businesses use their resources to buy influence in government and the media. Rather than the government governing the free market, the free market then governs the government.

This corrosive to the long-term success of our civilisation, yet it is endorsed by some as an extension of natural selection. Those who apply the survival of the fittest mindset to their own species – especially those at the top who justify their corruption of political systems in this way – overlook the fact that survival of the fittest leads to extinction much more frequently than it leads to survival. This is true even for otherwise successful apex predators (like T-Rex or Megalodon) because fitness is entirely dependent on the environment.

The propagators of this mindset appear to be attempting to using their head-start to outcompete the rest of their own species for access to resources. And what’s the end game? The creation of Elysium? Narrowing our gene pool to only incorporate a narrow range of genetic compositions will only raise the probability of actual extinction, rather than merely economic collapse.

And then there’s the knock-on effect of pollution and ecological collapse on the species we rely on for food. The simultaneous effect of the survival of the fittest mindset is to aggressively compete – to be the first to develop new technologies and weapons like AI, to be the first to colonise space. To gain access to the next generation of resources, and the energy to power it all. The consequence is that we are transforming the environment so dramatically that it’s shifting beneath our feet at a speed our civilisation has never before faced – climatic change unseen since the last Ice Age ended 12,000 years ago.4

Our atmosphere is already much warmer, and much more humid, with the increased rainfall, susceptibility to disease, rising sea levels, and widespread flooding that go along with it.

We’ve killed off most of the megafauna and thousands of other species; the UN’s Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services estimates that we’re set to lose another 1 million species unless we take remedial action. What happens when the environmental change – whether through the climate or through pollution – accelerates so quickly that we ourselves are unable to adapt? The institutions we’ve evolved, the political and economic developments that underpin modern society, that have created so much wealth and lifted billions of people out of poverty — these things can easily crumble under the shifting sands of the potentially irreversible environmental change we are creating in the name of a survival of the fittest mindset.

Any species can adapt out of a dead-end given enough time. As can any economic model. But we are running out of time. Our systems and institutions are changing too slowly, held back by the apex predators of our economy who are resistant to giving up their source of wealth. Too slowly to adapt to the pace of technological and environmental change. Just look at how long it took the tobacco companies to admit that cigarettes cause cancer, or how long it took oil & gas companies to admit that fossil fuel-derived greenhouse gas emissions contribute to atmospheric warming (many still obfuscate the truth today).

I don’t believe we will truly drive ourselves to extinction – at least, not immediately. We’re too adaptable, and too good at working together for that. Just as in Fallout, Mad Max, or Children of Men, some humans will likely survive in a post-apocalyptic wasteland, whether the apocalypse is caused by global thermonuclear war, or the global diaspora and military, political and economic unrest caused by a 4 degrees Celsius rise in global temperatures. But none of these dystopian futures look particularly appealing. Are we so hostile to the comparative paradise we live in today that we’re willing to risk everything and trade it for such a miserable existence, all in the name of the survival of the fittest?

Our civilisation dissolved, our resources exhausted, with Earth’s orbit filled with space junk shrapnel preventing future space travel, there will our descendants be, hanging onto the meagre existence we have left them, trapped on this planet with no way to escape until the next asteroid strikes. Surely, we can do better than that?

The dinosaurs got unlucky – they couldn’t have prevented their mass extinction event.

We can.

All it needs is a change in mindset.

Thank you for reading.

If you found this article to be thought-provoking, please consider sharing it with someone else who may be interested in its contents:

I also encourage you to become a free subscriber of my Substack, to get future articles delivered straight to your inbox:

This is also known as evolutionary suicide, but I find the term “evolutionary dead-ends” better illustrates the concept.

Neither a cat nor a tiger, a distant cousin of both – but I doubt that mattered to ancestral humans when they were being ambushed by one in the North American wilderness.

Actually, some scientists don’t believe that humans are responsible for the extinction of ground sloths, despite the fact that they survived in the Caribbean for thousands of years after humans wiped them out on the continent. I’d argue that only a scientist could look at the evidence and draw a conclusion which fails to account for the psychology of the average human, whether those humans lived 12,000 years ago or today. Put yourself in the shoes of those ancient hunters – just imagine the glory and excitement of heading out with your team with as many spears as you can carry and taking down a 3-tonne giant sloth – it would be one of the most intense boss battles of your life! The adrenaline rush must’ve been intoxicating.

Technically, the end of the Younger Dryas reversal.