How Everything Evolves: 1 — How Order Emerges from Chaos

How dynamics and emergence drive every evolving system

Ours is an emergent universe.

We live inside a nested set of emergent systems. The cells in our bodies are formed from dynamically interacting molecules, themselves formed from dynamically interacting atoms. The societies we inhabit are formed from dynamically interacting institutions and organisations, themselves formed from people dynamically interacting with each other and with the environment.

There are core concepts that underpin and explain the evolution of these systems; commonalities across the various scales of size, complexity, and time. This article is the first in a series — How Everything Evolves — that will illustrate some of these common threads and help us understand how they influence every system, both natural and man-made.

Let’s start, briefly, with the most fundamental element of the evolution of any system, whether complex or simple:

Time.

Time

We could start with a much deeper philosophical discussion here: what, exactly, is time? This is a question that currently puzzles the most highly respected physicists of our generation. We all intuitively understand how time feels, without needing to understand it at its most fundamental level.

For most purposes, it is enough to say that time is the rate of change of the state of any system. It sounds trite, but a minute is defined by the number of events that can take place within one minute — the second is literally defined by the timespan in which an atom of Caesium “vibrates” precisely 9,192,631,770 times. Of course, the number of events that can take place within a minute greatly depends on the scale of the system being examined. Your brain might oscillate up to 6000 times a minute while you’re concentrating; whereas an average of 8 successful passes are completed each minute in a game of professional football.1

Fundamentally, without the passage of time, a system does not update.

But what determines how a given system updates over time?

This leads to another core concept in evolution, one that is often misunderstood.

Entropy.

What is Entropy?

Many of have a vague understanding of entropy; it is often associated with the concept of chaos, or the gradual decay of systems over time, or the heat death of the universe.

These things are certainly relevant to entropy, but they are not synonymous.

At its most basic definition, entropy is simply a way of measuring the number of ways the elements of a system can be arranged.

If you arrange a single object in a line, there is only ever one arrangement.2 Beyond that, if we want to arrange multiple objects in a line, then the number of possible arrangements increases super-exponentially — faster than exponential growth — according to the number of objects.3

And that’s in one dimension — the number of arrangements increases even faster in two dimensions, because the geometric space in which the balls can be arranged is now part of the system, rather than just arranging them in a straight line. For a set of balls on a snooker table, there is one “perfectly ordered” arrangement of the balls — at the start of the game — and an uncountably large number of “disordered” arrangements of the balls once play has started.

This is important, because in the real world, every layer of the emergent evolving systems that comprise the universe occupy physical, three-dimensional space,4 dramatically increasing the number of possible disordered arrangements.

Within those disordered states, some arrangements are more likely than others — in snooker, there are many more possible random arrangements of balls on the table with a mixture of red and coloured balls (relatively disordered states) than arrangements where the red balls are all grouped at one side of the table (relatively ordered states).

Entropy is the term we use to describe how ordered or disordered a system is — “high” entropy describes states where there is a high degree of disorder, and “low” entropy describes more ordered states.

The Second Law of Thermodynamics states that, in a closed system, entropy must always increase — understood through this lens, this is then simply a statistical tool for describing the tendency for systems to evolve towards the types of states where there are a greater number of possible arrangements. So, really, entropy is less about chaos, and more about probability — it’s just that the chaotic states are much more numerous, and therefore much more likely.

Science communicators often talk about entropy as a driver of system evolution — that systems naturally evolve along trajectories that maximise entropy. But this is a shorthand that confuses effect for cause.

What happens in any system — say, a hot cup of tea with cold milk mixed in — is that the underlying configurations of the elements (the molecules in the cup) explore all the arrangements possible based on their present conditions. Entropy is just our statistical summary of that exploration, a way of saying that you are near-infinitely more likely to end with a cup of mixed, milky tea, rather than an arrangement with milk and tea molecules separated.

Entropy is a record of the evolving dynamics of the system, rather than the active driving force behind its evolution.

Once any system starts evolving, it explores all the configurations available to it based on the dynamics of its constituent elements and its present conditions. And this is how every element of the universe evolved.

Some of those configurations led to stable arrangements of matter like atoms, nebulae, stars and planets, guided by the fundamental forces of the universe — electromagnetism, the nuclear strong and weak forces, and gravity.

If you treat entropy as the driving force behind such evolution, the existence of such stable structures is a puzzle. How can order and stability emerge from systems being driven by the chaotic force of entropy?

The answer is that it is not entropy that makes things happen — it is things happening that make entropy.

The Paradox of Order

Given enough time, the patterns that govern the interactions between elements in a system in three-dimensional space cause a near infinite arrangement of patterns to form. And this is the key to understanding the paradox of order.

Unstable patterns decay relatively quickly, in any system — short-lived radioactive isotopes decay into other elements; lethal alleles kill embryos during development; companies that can’t balance the books collapse.

In contrast, a stable pattern only needs to form once in order to stick around — after clouds of gravitationally unstable dust collapse into stars, they can last for millions or even billions of years, balancing the collapsing force of gravity against the erupting energy released from nuclear fusion. A star can dynamically maintain its internal structure and evolve over time.

Once a system hits a tipping point, the temporal stability of the new pattern — a star — embeds it within the surrounding system. It becomes a permanent feature, and the system now evolves with this new feature as an element — solar systems, and galaxies.

Similarly, the first self-replicating chain of chemical reactions occurring spontaneously from proteins and sugars changed the evolution of the primordial soup — the leap from chemistry to biology was complete.

And this explains the paradox of how order emerges from chaos — through self-organising patterns. Quarks and electrons self-organise into stable atoms, which self-organise into stable chemicals, which self-organise into stable organic molecules, which self-organise into RNA and proteins and DNA, which self-organise into the full complexity of life on Earth.

The exact same dynamics apply to technological development in human civilisation. Every new technology changes the technological landscape, from water screws to radio transmitters, adds new possibilities and permutations, altering what it is possible to create in the future. We are seeing this happen in real time with AI.

Once replication or feedback loops occur like this within systems, complexity skyrockets, and the increase in complexity massively increases the possible configurations of the system, dramatically increasing its entropy.5

In this sense, given enough time, everything tends towards complexity. Each new layer of complexity builds upon prior patterns of self-organised order, expanding the number of possible future configurations of stable patterns for the system. And this leads us to emergence.

Emergence

Emergence is a property of complex systems where the behaviour of the whole system (the “macro” level) has properties that its individual components do not possess.

As an example, a protein has properties based on the geometric shape of folds in its large-scale structure — structure that emerges from the 3D assembly of its constituent atoms. The macro shape of each protein is difficult to predict based purely on the properties of the individual atoms themselves. This is the famously intractable problem solved by AlphaFold, winning Sir Demis Hassabis and John Jumper the 2024 Nobel Prize in Chemistry.

The properties of large-scale systems are emergent from the dynamics of the component interactions, not from the isolated properties of their parts — a second-order emergent property.

A proton is a stable, emergent pattern of subatomic particles, made from dynamically interacting quarks.6

An atom is a stable, emergent pattern of dynamically interacting protons, electrons and neutrons.

A molecule is a stable, emergent pattern of dynamically interacting atoms.

Life is a stable, self-organising, dynamic, emergent pattern in the interaction of specific molecules.

A cell is a stable, self-organising, dynamic, emergent pattern in the interaction of specific biological chain reactions.

You can follow this logic all the way to multicellular lifeforms, animals with nervous systems, conscious animals, social interactions, group dynamics, and the emergence of civilisation itself.

Each layer is a stable, emergent pattern built upon the dynamic interactions of the level below. And each layer has properties that cannot be predicted by the individual properties of subordinate layers.

The Limits of Reductionism

As I argued in The Evolution of Consciousness, this inability to model higher order systems based on individual components means we cannot model consciousness based on the properties of neurons; it’s an emergent property of dynamic neuronal interactions, not neurons themselves.

And this is the core principle — to understand emergence, we must study the patterns and dynamics, not just the components. Emergent behaviour is not reducible to its constituent parts.

A recent paper published by neuroscientist Erik Hoel supports this mathematically — the paper brilliantly demonstrates how higher order macro levels can have genuine causal power not contained within the individual elements.

This seems obvious — if I choose to throw a ball, then I am the cause of its movement on the level of my conscious decision-making, not on the level of my cells or atoms (which are merely the agents of my conscious action). But this has been very tricky to prove mathematically.

Hoel’s paper shows that higher levels of description can have more real causal power than lower levels because they filter noise out of microscopic subsystems, even in fully deterministic systems.

In this sense, emergence is the mathematics of interaction.

“You think that because you understand ‘one’ that you must therefore understand ‘two’ because one and one make two. But you forget that you must also understand ‘and.’”

– Sufi teaching story, from Donella Meadows’ Thinking in Systems: A Primer

In this context, it should be obvious that 1 + 1 = 2 is a simplification. It implies that a pair is the equivalent of two individuals, but it ignores that the pair — whether a pair of hydrogen atoms, or a pair of humans — will interact with each other in novel ways that cannot be predicted by the properties of the individual alone.

It is the dynamics between the interacting elements that define the emergent properties of any system — the geometry and chemical bonds in a molecule that do not exist in isolated, individual atoms.

Interaction creates novelty.

On the Origin of Life

To summarise:

Order initially arises in systems that evolve over time by chance, based on the properties of the dynamically interacting constituent elements of the system.

Order sticks around when the ordered patterns are dynamically stable over time, often driven by self-organisation.

Entropy is a measure of probability based on the increased likelihood of disordered states in any system, rather than representing chaos itself.

The increasing complexity created by increased order accelerates global entropy by creating more possible configurations, consistent with — but not caused by — the Second Law of Thermodynamics.

And this leads us to an important conclusion.

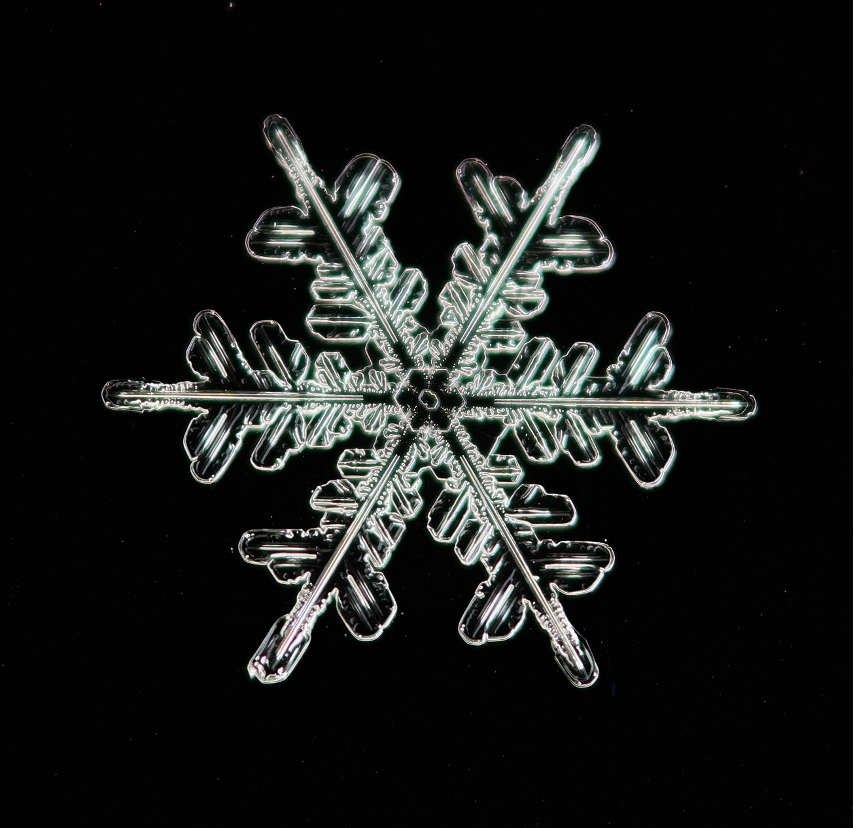

Many have viewed life as an engine of entropy. Organisms, like other ordered systems like cities or snowflakes, all locally reduce entropy (increasing order) while accelerating global increase of entropy (usually by accelerating energy transfer into the environment).

But this is only half-true.

Life did not first evolve to satisfy entropy.

Life, like every other stable, self-organising system in the universe, first evolved by chance, based on the dynamics of the underlying elements of the system in which it appeared (molecules, radiation, temperature, etc.).

Life stuck around because the chemical reactions contained within its self-organising structure are dynamically stable over time.

And life was permitted by the laws of the universe because this stable, self-organising structure increased global entropy.

This shows that coordination and structure do not restrict the freedom of an evolving system; counterintuitively, they amplify it.

The universe’s story is not one of decay and disorder, but of ever-more-efficient exploration of possibility and increasing complexity.

And I find that quite optimistic.

A final question: order arises from chaos, yes — but what factors influence the direction of evolution once order has emerged within a system?

We will cover this in the next article in the series; subscribe to Everything Evolves to make sure you don’t miss out:

If you found this article thought-provoking, please share it with someone else who may find it interesting:

And please share your thoughts in the comments:

Soccer, if you’re American

If we ignore its microscopic structure

This is because the formula for permutations of n objects is given by n!, the factorial function, where n! = n × (n - 1) × (n - 2) × … × 2 × 1, which increases faster than xn, the exponential function

Except maybe black holes, but let’s not go down that rabbit hole

A useful framework for thinking about this can be found in Assembly Theory, which measures the structural complexity of a system based on how it evolved, and shows how these systems can scale complexity across emergent layers.

If you want to know what a quark is, then join the club — physicists are still working on that one

It's interesting how "time is the rate of change of the state of any system" really clarifies time's foundational role across scales; such an insightfull take!

The answer is that it is not entropy that makes things happen — it is things happening that make entropy. Love this. So many cool nuggets in the article Nicholas. Well explained and written!