What is Mathematics?

Is it really the language of the universe? Or just a useful tool?

If you ask a mathematician: What is mathematics? You will receive a wide range of answers.

For Galileo, mathematics was “the language with which God has written the universe.” Similarly, today, theoretical physicist Michio Kaku describes it as the “language of nature”.

Taken to its extreme, this view leads some to believe that the universe is actually made from mathematics itself.

This deification of mathematics, however, obscures some fundamental truths. If the universe is mathematics, if all mathematical structures literally exist in some external, Platonic realm, then why do so many mathematical systems fail to correspond to anything in the physical world?

In contrast, there is another school of thought. In mathematician Errett Bishop’s words, “mathematics belongs to man, not God”. Or, to summarise philosopher Hartry Field’s argument, mathematics is used in science because it is useful, not because it is true.

At the extreme end of this view, mathematics is treated as an entirely human construct, a convenient abstraction, but not a true reflection of the physical universe.

But this too seems incomplete. If mathematics is purely a human abstraction, why can we use it to build particle accelerators and uncover deep truths about the structure of the universe? Why do certain equations so precisely model the motion of atoms, stars and galaxies?

This is the paradox. And unravelling it reveals something fundamental about both mathematics and the universe itself.

So, what is mathematics? Is it something we discover, a deeper layer of reality? Or something we invent?

This question has puzzled and polarised philosophers since Plato and Aristotle. And it continues to divide today’s leading theoretical physicists.

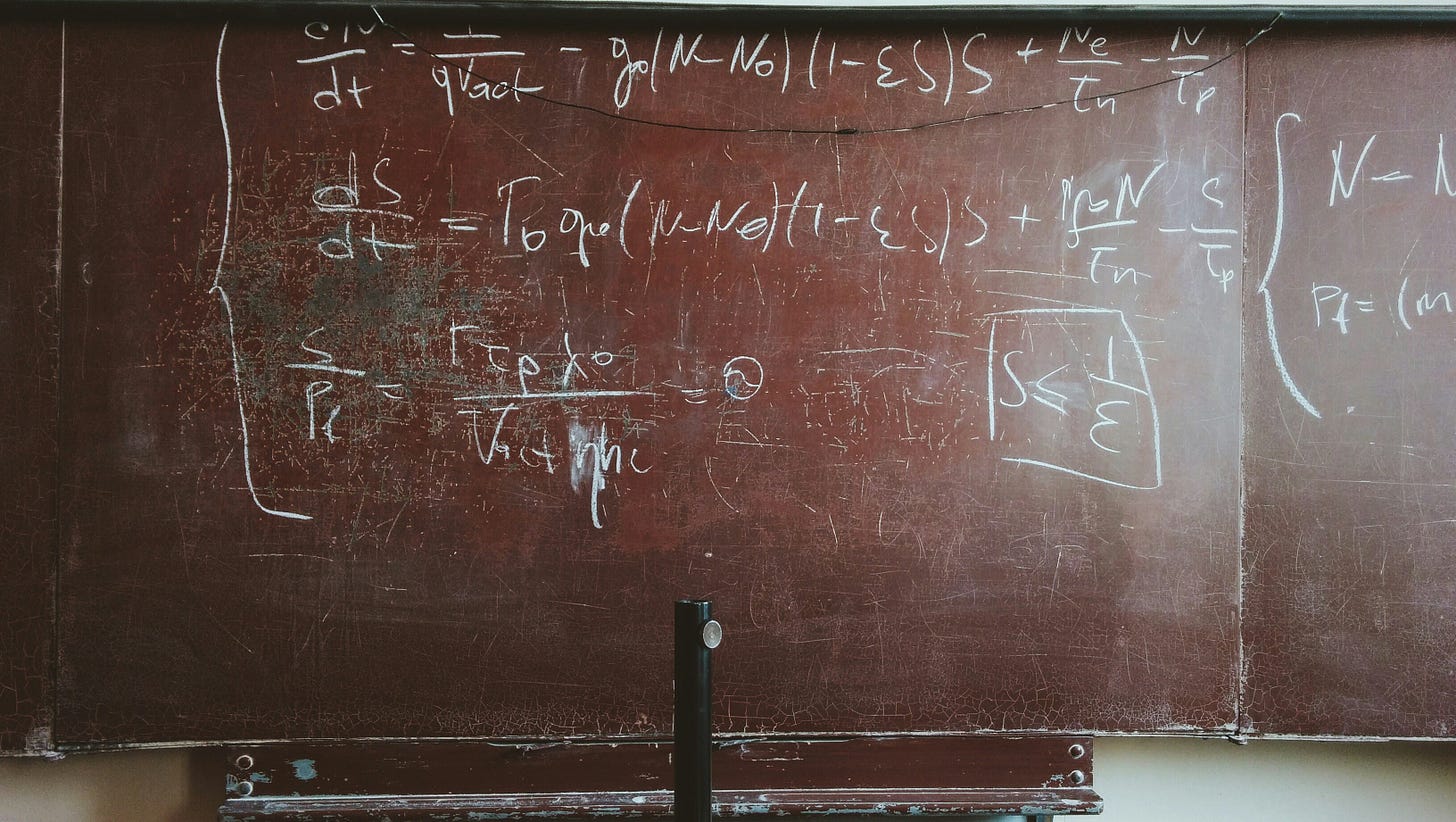

Like any good scientific investigation, we should begin with what we know: whether discovered or invented, every mathematical equation that we use — from 1 + 1 = 2 to the quantum electrodynamics action — first originated in a human brain.

So, let’s start there.

Mathematics as a Human Language

Human brains evolved over millions of years after diverging from chimpanzees. Somewhere in that time, we developed the ability to communicate using complex spoken language.

Many animals communicate, whether displaying emotions through body language or simple vocalisations, or transmitting information about the environment through chemical markers or even dancing.

What separates spoken language is that it enables the communication of a much greater range of abstract and layered complexity.1 It enables us to take the overwhelming, interconnected complexity of ourselves and our physical and social environment and break it down into comprehensible, communicable chunks. “This plant is poisonous, don’t eat it” conveys more specific and useful information than body language alone.

Human language even allows us to use abstract, non-physical concepts like “community”, “money”, and “economics” to coordinate actions between individuals within a group. However it evolved,2 it helped our species flourish because of that successful coordination.

This demonstrates something fundamental about how our brains work.

Long before we could speak, our ancestors’ brains evolved, in primordial seas, to make models of reality. To predict, navigate, and control the environment, to better ensure the survival of the genetic line.

Even without words, the brain categorises the environment to better navigate it: “food”, “threat”, “shelter”. Spoken language is then an extension of this process, labelling those categories and experiences for inter-mind communication.

Mathematics builds on these foundations. It is another language, designed to quantify and manipulate relationships between stable features of the world. Six apples shared fairly between two people always results in three apples each.

But “6 ÷ 3 = 2” is not a universal law. It’s a rule within a system we invented to express discrete relationships — useful for counting separable objects such as people and apples, but less applicable to physical systems like fluid flows or fractals.

Still, our ancestors lived in environments dominated by countable objects, not continuous patterns, so our intuitions and our mathematics evolved accordingly. Integer-based mathematical systems allow us to do useful things like keeping track of food, how many mouths need feeding, and who owes what to whom.

In this sense, mathematics cannot be separated from our human minds. It is internally consistent precisely because we designed it that way. Like logic or grammar, mathematics is rule-based — and we wrote the rules.

So, mathematics is a language. But it is not like other languages.

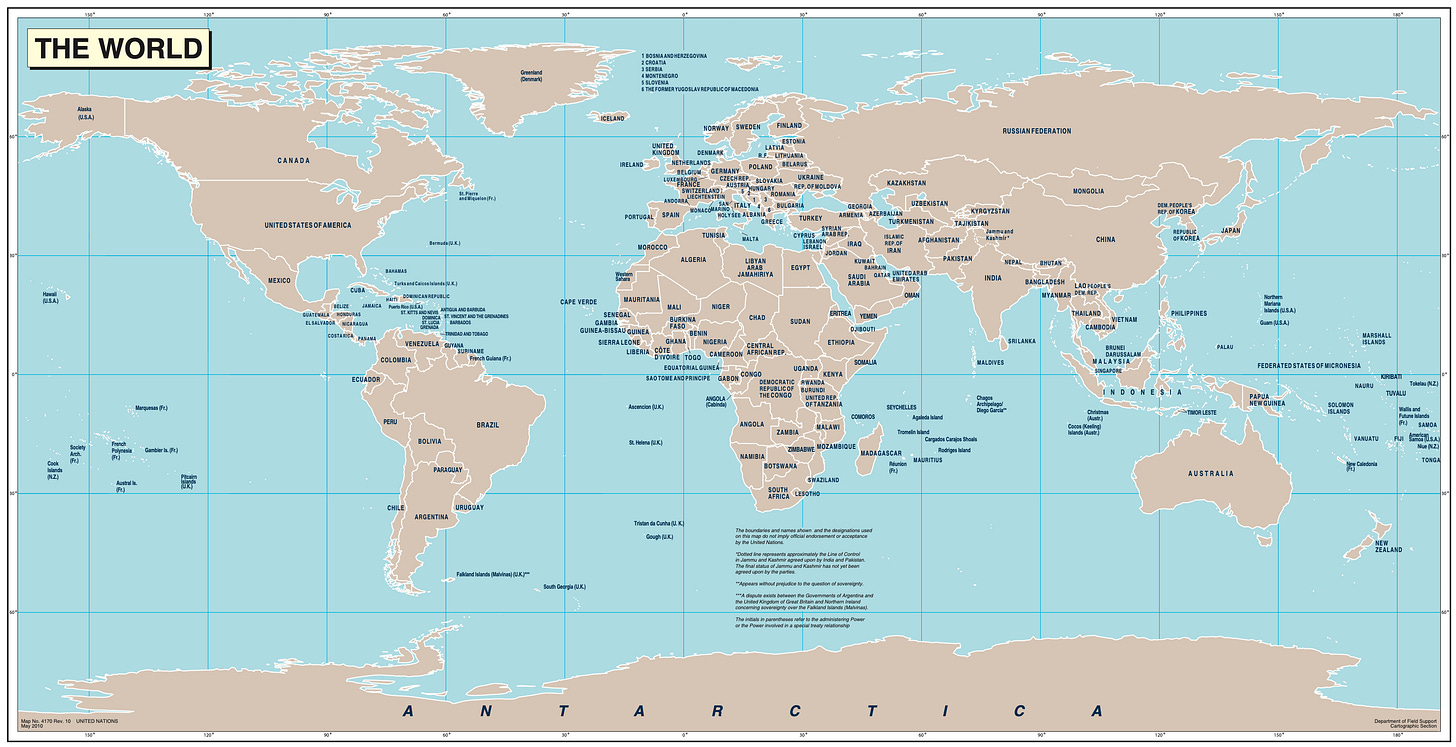

In natural languages, there are some things that are untranslatable; different cultures categorise the world differently before adding labels.3

On the other hand, mathematics has universal features. Whether you are using Arabic numerals, Roman numerals or binary, 5 + 5 always equals 10. The symbols may vary, but the relationships they express do not.

This implies that any intelligent species might converge upon some similar form of mathematical reasoning, a way of abstracting and quantifying relationships in the world. And, indeed, other animals here on Earth can perform basic numerical operations.

Which brings us back to other side of the paradox: if humans invented mathematics — and we did, demonstrably — then why is it so good at describing reality?

Is reality made of mathematics, waiting for intelligent life to discover it?

Or is there another reason?

The Unreasonable Effectiveness of Mathematics

Nobel Prize-winning theoretical physicist Eugene Wigner captured this puzzle in his 1960 paper “The Unreasonable Effectiveness of Mathematics in the Natural Sciences”, observing that the mathematical structures used in theoretical physics often lead to further advances in both theory and empirical prediction.

One example he gave was Newton’s law of gravitation.4

Though originally developed to describe falling bodies on Earth, Newton’s mathematical formulation also successfully described the motions of the planets with predictions that were, according to Wigner, “accurate beyond all reasonable expectations”.

For many in the physics and mathematics communities, this suggests that there are deep mathematical truths built into the foundations of reality. After all, the thinking goes, there is no obvious reason why equations invented by humans should so precisely mirror the workings of the physical universe.

Except, of course, there is a reason. It might not be obvious, but neither is it mysterious. Why is it that Newton’s observations of a thrown rock here on Earth also describe the motion of the moon orbiting the Earth?

Because the same physical relationship underlies both — gravity.

The universe has specific, consistent properties, and the gravitational attraction between massive objects (caused by the warping effect of mass on spacetime) is one of those properties.

When Newton invented his equation, he did so to model the gravitational relationship between falling objects and the Earth. But what he then discovered is that this relational property — gravity — is universal in nature. As such, the equation could be applied far beyond the scope of its original creation.

And this is the real heart of the matter. Some mathematical structures correspond to real, stable, physical relationships, not because those structures underpin the universe, but simply because consistent relationships can be described by mathematics.

So, in this sense, Wigner may have missed the mark: once we recognise the stability of physical laws as the underlying cause, the effectiveness of mathematics in the natural sciences becomes entirely reasonable.

This is broadly the position of structural realism, most clearly articulated by philosopher John Worrall in 1989. The idea is that mathematics provides a reliable model for describing the stable relational structure of the physical world — the patterns that persist even when our theoretical explanations evolve.

Newton’s laws of gravity were eventually superseded by Einstein’s general theory of relativity, which provided more accurate predictions, but the structural relationship between mass, distance, and gravitational effect remained recognisable (and describable).

And this leads us to another crucial point: the fact that Einstein’s model approximates Newton’s simpler model in low-speed, low-gravity conditions reveals the danger of treating mathematics as a literal representation of the universe.

To do so is to mistake the model for reality.

Mistaking the Map for the Territory

Using mathematics to describe the universe is not the same as the universe being made from mathematics. And yet there are plenty of prominent hypotheses that make this fundamental error in logic, perhaps most prominently Max Tegmark’s “mathematical universe hypothesis”, and this recent article on Vlatko Vedral’s literalist interpretation of quantum mechanics.

This error — mistaking the model for reality — is an extension of Plato’s ancient belief that there exists a realm of perfect, ideal forms where all mathematical objects literally exist, and the universe emerges from those forms.

But it is just that — a belief, without evidence, and without any acknowledgement of the evolved, linguistic origin of mathematics.

This is in direct contrast with science, where we build and test models against physical evidence. Any model that seeks to explain everything in the universe, a true theory of everything, must be able to account for all of the available evidence.

And to say that the universe is made from mathematics ignores some fundamental evidence.

Mathematician Kurt Gödel famously proved, with his incompleteness theorems, that any mathematical system that can describe basic arithmetic cannot be both complete and self-consistent. There will always be true statements it cannot prove from within itself, and it cannot even prove its own consistency. Mathematics, in other words, has limits baked into its foundations.

So the idea that the universe is mathematics — a perfect, closed, self-revealing structure — runs directly into Gödel’s result: mathematics cannot even fully reveal itself, let alone guarantee a complete description of reality.5

In addition, many elements of the universe resist being modelled mathematically. Even something as deceptively simple as the three-body problem, which predicts the motion of three gravitationally interacting bodies, has no general closed-form solution. There is no explicit formula that can describe their motion over time.

If modelling just three objects is so difficult, how can we expect a neat mathematical formula to fully capture the complexity of systems like weather, ecosystems, or human civilisation?

And, finally, there are infinite branches of mathematics that do not correspond to known physical reality.

Take the imaginary number, i, defined as the square root of minus 1. It is difficult to overstate how useful i is for computing things like rotations, oscillations, and wave phenomena. But there is no corresponding physical object in the real universe that can be squared to give a negative number.

Similarly, mathematicians routinely construct models in infinite-dimensional spaces, or in universes with four, ten, or even twenty-six spatial dimensions. Meanwhile, in the physical universe, we only observe three (plus time).

These examples show that most mathematical models are artefacts of logic, internally consistent frameworks for describing relational properties, and not fundamental features of the cosmos.

And this matters.

Because the dangers of conflating the map for the territory are profound for scientific progress. When symbolic models are interpreted literally, they can lead us to conclusions that are unscientific and not representative of reality.

The most striking example is the ancient geocentric model of the solar system. What most people forget is that it was a good model for predicting planetary motion. It used deferents and epicycles to accurately predict the positions of the planets in the sky.

The mathematics worked, but it was entirely based on a false premise: that the Earth was the unmoving centre of the universe. The model’s internal logic was sound, but the metaphysical, literalist interpretation was wrong.

It mistook the model for reality.

This is the risk. Yes, good predictions can come from bad assumptions. But when we forget that models are tools, and not literal truths, we preclude ourselves from true understanding.

What is mathematics?

So, what is mathematics?

It is neither transcendent nor entirely fictional.

Mathematics is a structured system, built by minds that evolved within the universe, that describes the relationships between entities (physical or imagined).

At its best, mathematics can describe real relationships with remarkable fidelity, revealing that the universe has consistent, describable properties.

But mathematics is not reality. It is a tool — one that enables predictive power when it successfully models real physical structure.

And the fact that it is such a successful tool is exactly why we must treat it with both respect and caution.

Because mistaking the model for reality is, in my view, a central reason why humanity has yet to reconcile general relativity with quantum mechanics.

If mathematics is not reality, and quantum mechanics is a mathematical framework, what does it mean when we treat quantum mechanics as a complete theory of reality?

What happens when we confuse predictive success for ontological completeness?

What happens when a tool designed to work around the limits of observation is taken as a literal description of the world?

We will cover this in Part II of this series.

Subscribe to Everything Evolves to make sure you don’t miss it:

If you found this article thought-provoking, please share it with someone else who may find it interesting:

And please share your thoughts in the comments:

Other advanced social animals also appear to have some form of spoken language; elephants have names, for example.

If you want to drive yourself mad, you can familiarise yourself with the many, many theories as to how, when and why human language evolved; the lack of direct evidence makes this a challenging task.

Like wabi-sabi, the Japanese aesthetic concept centred around finding beauty in imperfection and impermanence. It taps into a rich cultural and religious history, with roots in Zen Buddhism, and so defies a direct translation into English.

It is worth emphasising that Gödel’s theorems apply to formal systems, rather than the physical universe itself, but any identification of the universe with such a system inherits its limitations.

“I thought I killed that thing 90 years ago??!”

I think you characterized the three body problem and Godels incompleteness theorem poorly. "There is no explicit formula that can describe their motion over time", aren't our laws of physics able to describe their motion over time? We run into issues with computation? Maybe you are making the same mistake you talk about in the article, just because it is difficult to compute doesn't mean that the laws aren't correctly describing it